Bill Walsh: 2018 Hall of Fame inductee

Bill Walsh was a man of style — so dedicated to his craft that when he wasn’t editing copy for The Washington Post, he was writing three witty books about copy editing, posting to his renowned website, The Slot, or tweeting about grammar.

Walsh, a 1984 graduate, died of cancer in 2017 in Washington, D.C. He was 55.

His books “noted evolutions and devolutions of language, the indispensability of hyphens and his hostility toward semicolons. ... By many accounts, Mr. Walsh stood at the zenith of his profession,” the Post wrote in its obit.

“Copy editors are the unsung heroes of my profession, the folks who ensure that our work is as pristine and accurate as possible,” said Emilio Garcia-Ruiz, Post managing editor. “With Bill, we lost one of the giants in the field.”

The American Copy Editors Society (ACES) awarded Walsh one of its highest honors, the Glamann Award, for contributions to the field of editing in 2017 and named a scholarship after him.

Walsh helped edit several Pulitzer Prize-winning projects, including a series on NSA surveillance that won for public service in 2014. He served as the copy chief for the Post’s national desk from 2003-2008 and chief of the night copy desk after that. He joined the Post in 1997 as a copy editor and designer, then became business copy chief.

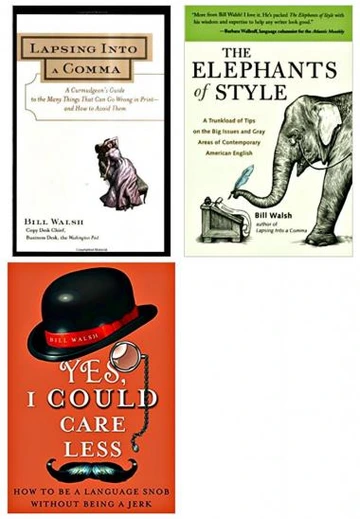

He wrote three books: “Lapsing Into a Comma” (2000), “The Elephants of Style” (2004) and “Yes, I Could Care Less: How to Be a Language Snob Without Being a Jerk” (2013).”

He started The Slot (theslot.com) in 1995 and became a sought-after guest speaker on editing. He tweeted several times a day about style issues.

“In a way, all literate people are copy editors, whether they are writers rewriting their own work or simply avid readers noticing a typo on a cereal box” Walsh said.

Walsh began at The Phoenix Gazette on the night police beat but soon joined the copy desk. When he left the Gazette in 1989, he was assistant news editor for design. At the Washington Times he started as assistant copy chief and rose to copy chief, a position he held for five years before moving to the Washington Post in 1997.

At UA, he minored in philosoophy and won the Mark Finley Gold Pen Award for best beginning news writer in spring 1982 and the William Hattich Award for Professionalism in 1983-84.

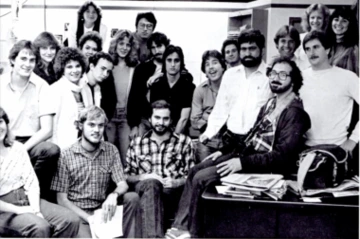

Walsh also worked as a copy editor for the Arizona Daily Wildcat, which inducted him into its Hall of Fame in 2006. In a Wildcat staff photo below, he is in the second row, third from left.

– Mike Chesnick, ’84

BILL WALSH: IN HIS WORDS

CAREER ADVICE

"I suppose my path toward a copy-editing career was about as straightforward as it gets. I spent four years getting a bachelor's degree in journalism at a college known for its journalism program, I got a job on the college newspaper as soon as I could, and I got a summer internship (actually, two summer internships) at a major metropolitan daily -- which hired me right after graduation. I paid my dues on the reporting side, and then I became an editor.

"If you're just starting college (or still in college mode, no matter what your age) and you want to be a copy editor when you grow up, make "internship" your mantra. If the place that hires you as an intern likes you, that place will hire you full time. If the fit isn't quite so nice, you'll have invaluable experience and an invaluable addition to your resume."

"Nothing you learn in a journalism class will be anywhere near as valuable as actual experience, which brings me to the other part of my experience you should strive to emulate: Join the school paper. At the University of Arizona, my alma mater, the paper is an independent entity supported by advertising revenue. I learned my future job by actually doing that job, and that's a heck of a good way to learn. ... Even if you end up at a college where the paper is more of a J-department organ, the experience is still the thing. Get it."

ABOUT GETTING CANCER

"I have had a great life ... a great wife, a great family, a great job, etc., etc. I would not trade 55 of these years for 75 or 85 or 95 of what's behind Door No. 2."